Understanding Budget Deficits and Interest Rates

Note: When I wrote this explanation of budget deficits and interest rates in 2007 as a chapter of my book, Lessons from a Road Warrior, we were in a different world where budgets mattered, at least a little. We argued about deficits of $100 billion or $200 billion, and never used the word ‘trillion’ in polite conversation. But now we are in a different world. The Treasury Dept. sold trillions of dollars in bonds to finance bailout programs for corporations and banks during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis; they did so again during the COVID pandemic to put checks in people’s mailboxes and to finance massive payments to real and imaginary businesses. A large portion of those bonds were purchased by the Federal Reserve, by taking on the authority to add all sorts of assets to their once-pristine balance sheet in the name of ‘Quantitative Easing.’

I decided to leave the numbers and the charts unchanged from my 2007 examples in part to highlight the fact that, although today’s numbers are many times larger than they were, the analysis remains unchanged. Balance sheets are still huge compared with flows of funds like savings, investment, and the budget deficit. The national debt is still a small fraction of total assets. It still takes a huge amount of government borrowing to move the needle on interest rates. The most important question for interest rates is the same today as it was then, whether anything is going on to change people’s willingness to hold the stock of securities they already own, not how many new ones the Treasury will sell this year.

The textbooks have it wrong

Textbooks have it wrong when they teach students that interest rates are determined by the supply and demand for credit. For example, a leading finance textbook (Investments, by Bodie, Kane and Marcus) states:

“Forecasting interest rates is one of the most notoriously difficult parts of applied macroeconomics Nonetheless, we do have a good understanding of the fundamental factors that determine the level of interest rates.

- The supply of funds from savers, primarily households.

- The demand for funds from businesses to be used to finance investments in plant, equipment, and inventories (real assets or capital formation).

- The government’s net supply of or demand for funds as modified by the actions of the Fed.”

These statements are wrong. Had you acted on them to structure your investments over the last 30 years you would have lost all your money. Interest rates are simply a calculation we make from asset prices, as I explained in a recent post. Asset prices are determined in asset markets by existing asset supplies and the demand to hold existing assets. In spite of what the textbooks tell you, throughout history, the correlation between interest rates and deficits is actually negative; i.e., higher deficits are associated with lower interest rates. The drawings below explain why.

Interest rates are not determined by savings rates and are not determined by the demand for credit. As a logical matter, it is debt, not deficits, along with people’s demand to hold different types of assets, that determine interest rates.

Budget deficits in the ranges we have historically seen them—a few hundred billion–don’t matter much for the economy. Not for interest rates. Not for growth. The multi-trillion dollar bond markets don’t care at all whether the government is a net seller or a net buyer of $100 billion in new Treasury securities in a given year. They care whether the people who own the old paper today are still going to want to own it tomorrow. And that will depend on whether something happens to change people’s minds about future after-tax returns on bonds relative to other assets–period. The rest is all rounding errors. Nothing else matters.

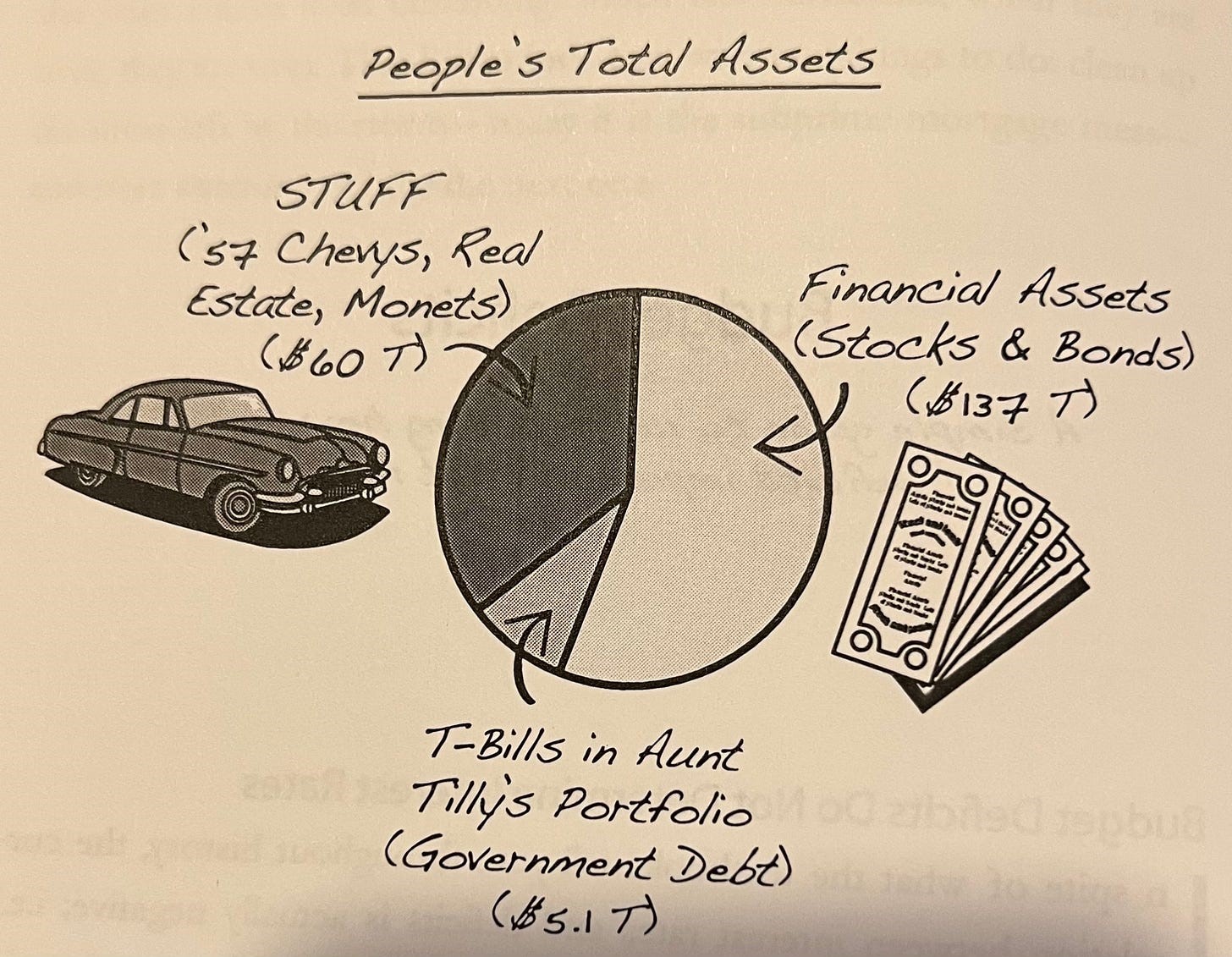

When the Treasury holds an auction to finance a deficit, they print and sell new T-bills or other Treasury IOUs (notes and bonds) to investors like Aunt Tilly. This isn’t the first time the government has borrowed money from private citizens. Aunt Tilly and other investors already own a huge stock of old T-bills—$5.1 trillion worth at the end of 2007—that we call the national debt, as shown in the above graphic. At the end of last year, there were $9.2 trillion of old T-bills outstanding—the government’s accumulated borrowing since the time of George Washington. Of those, $5.1 trillion, or 55%, was held by private investors like you, Aunt Tilly and me.

New treasury paper and old treasury paper are perfect substitutes to investors. Not almost perfect substitutes—perfect substitutes. In practice, they are indistinguishable in the market. T-bills, notes and bonds are also pretty good substitutes for many other securities owned by investors, including agency securities, corporate securities, municipal securities and CDs. These, in turn, are substitutes, to some degree, for equities, foreign securities and tangible assets in the minds of investors. When you buy a bond, you shop for its issuer, its maturity date, its call provisions, its tax features, and its yield—not its model year. This means that new bonds and old bonds that are the same in every other way must sell at the same price. Arbitrageurs make sure they do.

It’s like the commercial where the dad asks his teenage son to go to the local gas station to put gas in the family car. Hours later, the dad is still standing in the driveway when his son returns with the explanation, “But Dad, you didn’t want me to mix the new gas with the old gas, did you?”

Bond investors mix the new bonds with the old bonds all the time.

Flow-of-funds is a theory to explain the price of new bonds. Portfolio balance is a theory to explain the price of old bonds. But in the real world, there can only be one price for all bonds. Which theory wins? Portfolio balance, because almost all bonds are old bonds. The important question is not whether the government will borrow money this year. It is what price it will take to make Aunt Tilly—and all the other investors who owned T-bills yesterday—still want to own today’s stock of T-bills tomorrow.

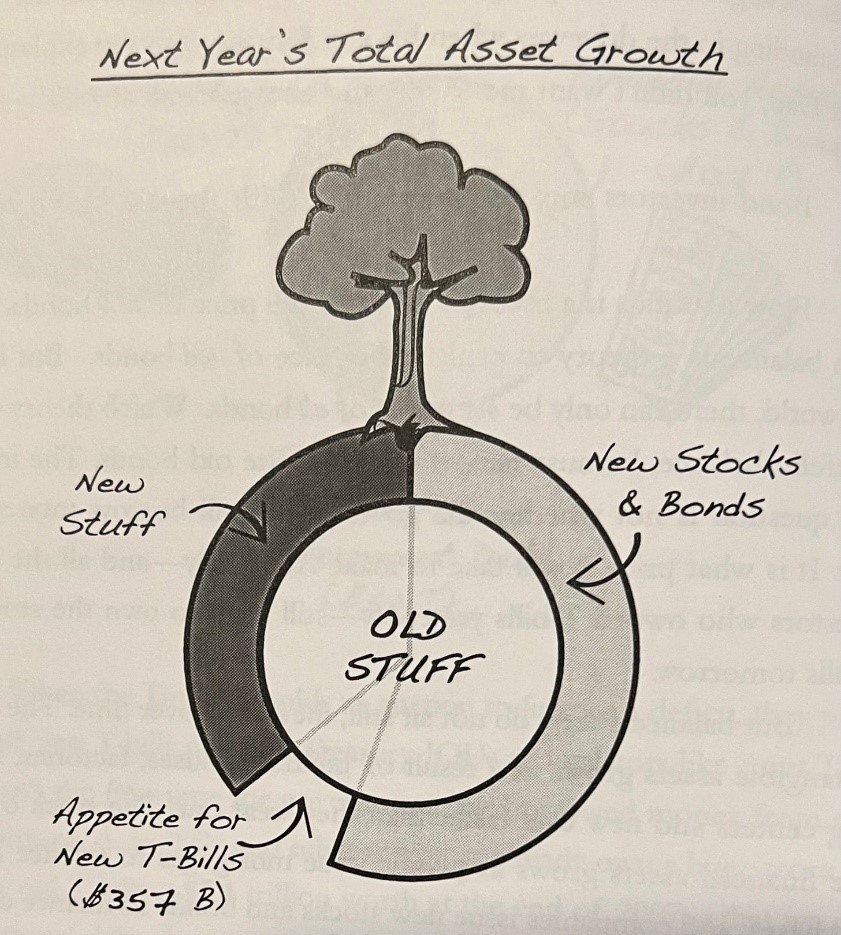

But balance sheets do not sit still; they grow over time. The stock of tangible assets grows because we build houses, factories, shopping centers and new cars faster than they wear out. The stock of private financial assets grows as people issue mortgages to finance home purchases, and companies issue new stocks and bonds to finance capital spending, home construction and durable goods production at a faster rate than the old ones mature. We create new government securities to finance the budget deficit, or we destroy them by using a budget surplus to buy back debt.

As our net worth grows, so does our appetite to hold all assets. This growth is represented by drawing a second pie chart, below, showing the larger stock of tangible and financial assets than we held last year. Historically, U.S. balance sheets have grown at about 7% per year.

Higher net worth gives investors like Aunt Tilly an appetite to own more T-Bills too, as illustrated in the drawing. You can think of this appetite as thousands of Aunt Tillys standing in line in front of the Treasury building, waiting to place orders for the new T-bills that the government will sell next year (to add to the ones they already own).

That appetite is larger than most people think. If net worth grows 7% next year, as it has done historically, investors will want to increase their holdings of T-bills by $357 billion, from $5.1 trillion to just under $5.5 trillion.

If the Treasury issues just enough new T-bills to satisfy Aunt Tilly’s appetite, then everyone will go away happy. There will be just enough T-bills to go around. Prices will remain the same as they were last year. Interest rates will remain unchanged.

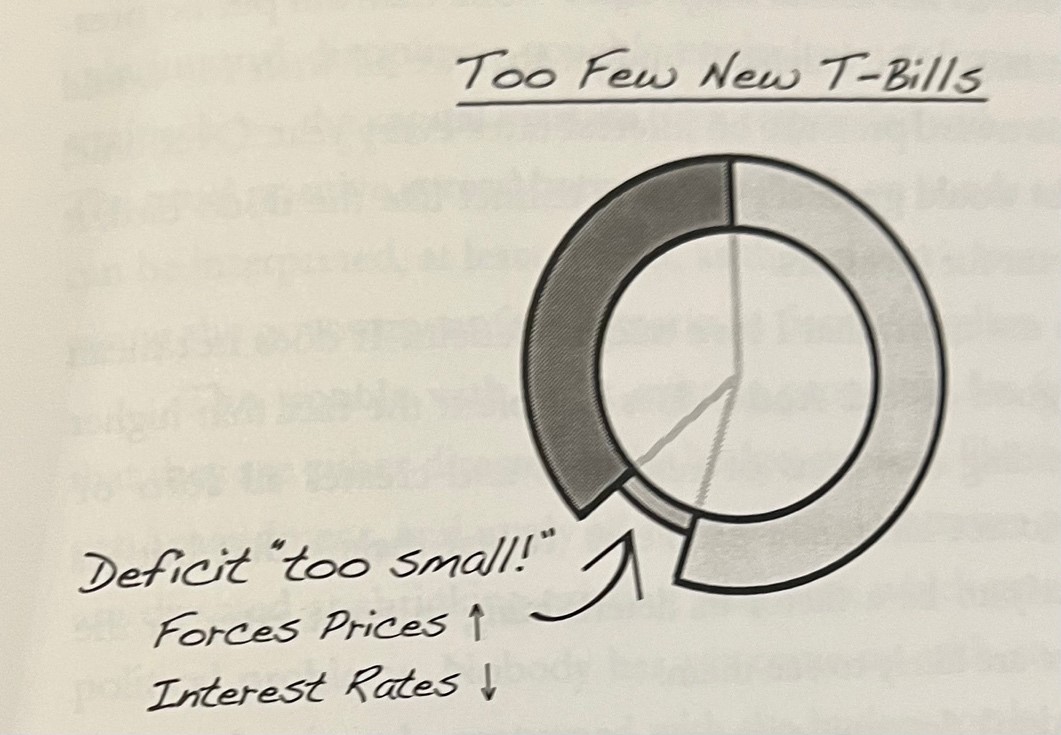

But what would happen if the treasury issued too few or too many T-bills to satisfy investors’ appetites? If there were too few T-Bills for sale due to a smaller government deficit, then Aunt Tilly would wrestle with the other investors for the limited supply. This would drive T-Bill prices up and interest rates down, as shown in the graphic below.

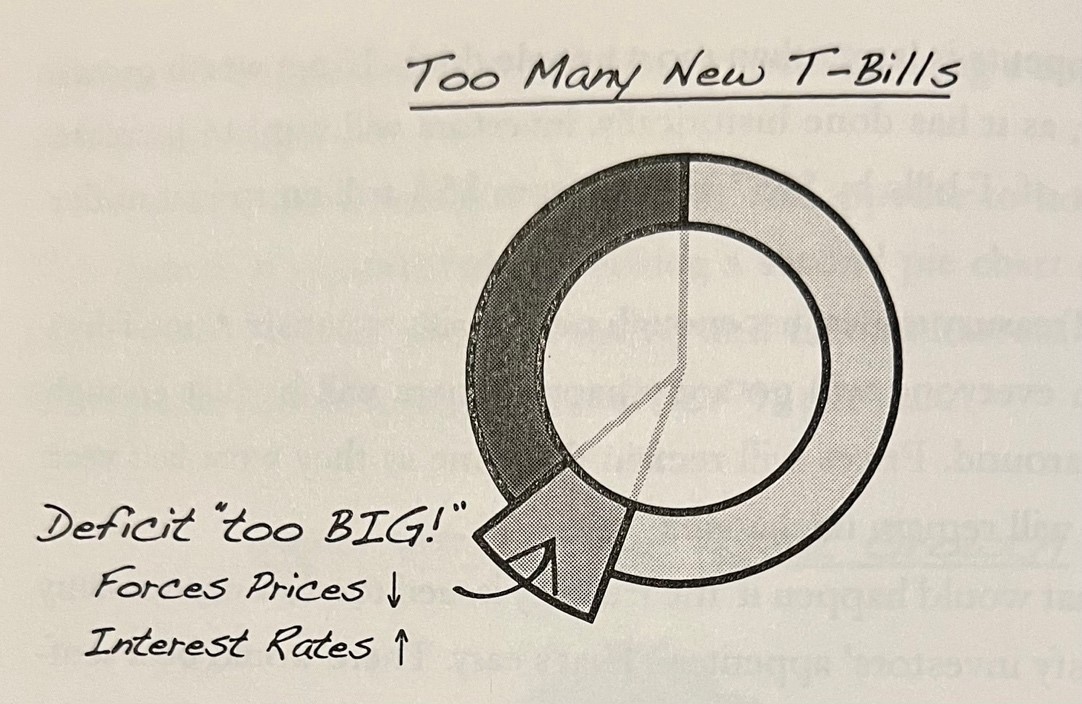

If the government ran a much larger deficit and there were too many T-Bills for sale, then the Treasury would be forced to lower their asking price to sell their inventory, as shown in the graphic below. T-Bill prices would fall and interest rates would rise.

It is only to the extent that budget deficits exceed Aunt Tilly’s appetite for new securities that they can be said to push interest rates up at all. In our example, we can think of the $357 billion from the previous example as the interest rate neutral budget deficit—one that will put no pressure on interest rates. The balanced budget that we all wish for would exert downward pressure on interest rates every year. Over time, government debt as a percentage of total assets would gradually become extinct like the dodo bird; it would be irrelevant for investors.

This does not mean that I love budget deficits. It does not mean that deficits are good or bad. And it does not blunt the fact that higher government spending uses tons of resources and creates all sorts of incentive and resource allocation problems. It just means that budget deficits are unlikely to be a factor in determining interest rates in the range in which we have historically seen them.

If deficits don’t determine interest rates, then what does? The answer is any factor that could drive a wedge between the relative returns on different assets. Higher inflation does that by increasing the return on tangible assets (i.e., the gain on owning a home raises its return) relative to returns on securities. That makes people sell securities to increase their holdings of real assets, like we saw during the 1970s, which drives interest rates higher. As a second example, lower income tax rates increase the after-tax returns on taxable securities relative to real assets, for example, because people are forced to report all income from securities on their tax forms but are not required to report the value of living in their home or unrealized gains from a home sale as taxable income. This will drive interest rates lower. As a third example, rising productivity growth can quicken net worth growth, which will increase Aunt Tilly’s appetite for all assets and drive interest rates lower.

Dr. John

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of Dr. John Rutledge. Assumptions made in the analysis are not reflective of the position of any entity other than Dr. Rutledge’s. The information contained in this document does not constitute a solicitation, offer or recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security or investment product, or to engage in any particular strategy or in any transaction. You should not rely on any information contained herein in making a decision with respect to an investment. You should not construe the contents of this document as legal, business or tax advice and should consult with your own attorney, business advisor and tax advisor as to the legal, business, tax and related matters related hereto.